Lab Session 1 - Introduction to Python

Contents

Lab Session 1 - Introduction to Python¶

Monday 01-24-2022, 11AM-1PM & 2PM-4PM

Instructor: Facundo Sapienza

Welcome to Stat 159/259! This is our first lab, so for today we will focus in setting you up in Github and make some practice in Python. The menu for today is

Setting up GitHub Account. If you want to learn more about how to work with GitHub and how GitHub internally works, we recommend you to take a look to The curious coder’s guide to git. After we all have a GitHub account, we will ask you to complete this form so we can add you to GitHub Classroom.

Warming up with Python. We will follow the Python tutorial written by Jake VanderPlas, A Whirlwind Tour of Python. We also invite you to play with the PythonTutor, where you can see how variables are referenced to objects as you write your code.

Debugging in Python/iPython.

Debuggin with pdb

Jupyter debugger

Remember we will be working in the JupyterHub for the full course, which has the libraries and tools we will be using during the semester. Why do we use the Hub? Well, it is quite convenient since you don’t need to install anything in your personal computer and you don’t need to worry about having installed all the required packages with their right version.

As we have already mentioned, we are going to use Python for all the projects and homeworks in this course. However, it is important to remark that many of the concepts we will see in this course apply to other programming languages too (Julia, R, C, etc). Some good reasons for working in Python include

Interpreted instead of compiled

Clean syntax

Object oriented (attributes + methods), convenient language constructs

Variables can access large data structures by reference, without making a copy (speed and memory efficient).

1. Setting up GitHub¶

If you don’t have a GitHub account yet, you can create one following this link (please DON’T use github.berkeley.edu). You can configure your preferences by using

git config --global <setting> <option>

For example, you can configure your email and

!git config --global user.name "Facu Sapienza"

!git config --global user.email "fsapienza@berkeley.edu"

For this course, we will be using GitHub Classroom. Once you all have a GitHub account created, we will add you to the repository for the course.

Once you have your GitHub account, please take a few minutes to complete this form.

The way we have to authenticate push/pull from the hub is by using this github-app-user-auth, a tool developed by @yuvipanda. Here’s how you can use it.

Go to https://github.com/apps/stat159-berkeley-datahub-access, and ‘Install’ the app. Give it access to whichever repositories you want to push to. You can come back and add more repos here later if you wish.

Login to stat159.datahub.berkeley.edu, and open a terminal.

Run github-app-user-auth on the terminal. It’ll tell you to open a link in your browser, and input a 6 character code it gives you in the page opened.

Once done, ‘Accept’ and it’ll ask you if you want to authenticate.

Once accepted, you’re done! You can now push to the repositories you gave access to in step 1 for the next 8 hours or until your server stops from inactivity! We’ll hopefully have a quick ‘sign in’ button at some point that can make this a bit more streamlined, but this should work nicely already.

2. Warming up with Python¶

For today’s session, we will follow A Whirlwind Tour of Python. You can see the contents of the book online, but you can also clone the repository of the book with the following command

git clone https://github.com/jakevdp/WhirlwindTourOfPython.git

Whenever you are doing this from the terminal or a notebook, remember to run this command from the directory you want the repository to be cloned.

It is important that you are familiar with the contents of chapters 1-8, which include some introductory python syntax and data structures. If not, please take a few minutes to go thought these notebooks and get familiar with them. These concepts include:

Basic operations (arithmetic, comparison, assignment, …)

Manipulation of simple data structures (lists, dictionaries, tuples)

Control flow (for loops, conditional statements)

## Simple Python code examples

## ... [To do during the lab]

2.1. Functions¶

For this part of the lecture, we recommend following Chapter 9. As we write more and more code, keeping track of what each piece is doing can became quite difficult. Functions allow us to encapsulate pieces of code that are responsible for addressing a more specific task. Then, a nice piece of code looks like different functions (sometimes concatenated one to each other) doing different tasks in order to archive a final mayor goal.

Functions receive different kind of arguments. The scope of this variables is always local, meaning that the variable name is declared just inside the function.

### .... [To do during the lab] Construct the following function

from math import gcd # we import the great common divisor function from math

def get_coprimes(L, d=2):

"""

Function to extract the coprimes elements of a list with respect to some give integer

Arguments:

- L: list with integers

- d: integer agains with the coprimality is evaluated

Outputs:

- res: list of subelements of L that are coprime with d

"""

res = []

for x in L:

if gcd(x,d) == 1:

res.append(x)

return res

L0 = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

get_coprimes(L0)

[1, 3, 5]

get_coprimes(L0, 3)

[1, 2, 4, 5]

A few comments about this last example:

Suppose we want to ignore the trivial case of every number being coprimer with

1. What can we do then? Do we add another conditional statement?What do we do if

Lhas negative values?What do we do if there are values in

Lthat are no integers?Can you think in ways of implementing

get_coprimesby using a different kind of data structures?Is it possible to extent the scope of the variables inside the function (eg, to obtain the value of

resinsideget_coprimesoutside the scope of the function)?

We can solve some of these problems by hand. In the next section we will see how to add exceptions for conflictive cases.

Something really useful about functions in Python is that we can add flexible arguments. These are divided into

Simple arguments:

*argsKeyword arguments:

**kwargs

def catch_all(*args, **kwargs):

print("args =", args)

print("kwags =", kwargs)

if len(args) == 3:

print(args[1])

print(kwargs['b'])

catch_all(1, 2, 3, b=1.1, c=1.2)

args = (1, 2, 3)

kwags = {'b': 1.1, 'c': 1.2}

2

1.1

def sum_args(*args, **kwargs):

res = 0

for x in args:

res += x

if "factor" in kwargs.keys():

res *= kwargs["factor"]

return res

sum_args(1, 2, 3, 5, factor=1)

11

We can also define anonymous functions, usually referred by the symbol lambda. This are useful for different things (for example, we will see how useful they are when dealing with dataframes in Pandas)

add_one = lambda x: x+1

add_one(1.2)

2.2

sorted(L0, key = lambda x : x%2)

[2, 4, 6, 1, 3, 5]

2.2. Errors and Exceptions¶

Different kinds of errors that occur as we write code include syntax, runtime and semantic errors. Specially for runtime errors, Python give us a clue about what kind or error may happened during the execution of our code. For example,

1 / 0

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [37], in <module>

----> 1 1 / 0

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

my_dict = {'a':1, 'b':2}

my_dict['c']

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [38], in <module>

1 my_dict = {'a':1, 'b':2}

----> 2 my_dict['c']

KeyError: 'c'

my_dict + {'c':3}

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [39], in <module>

----> 1 my_dict + {'c':3}

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'dict' and 'dict'

There are many more different kind of built-in exceptions in Python. You can find some more examples in this link. A general RuntimeError is raised when the detected error doesn’t fall in any of the other categories.

There are different ways of dealing with runtime errors in Python, there include the

try…exceptclauseraisestatement

a = 1 # numerator

b = 0 # denominator

try:

print("I was here")

a / b

print("Was I here?")

except:

print("Something wrong happened")

I was here

Something wrong happened

a = 1

b = 0

if b == 0:

raise ValueError("b must be different than zero.")

a / b

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [42], in <module>

2 b = 0

4 if b == 0:

----> 5 raise ValueError("b must be different than zero.")

6 a / b

ValueError: b must be different than zero.

In the following example, we use both try…except and raise, but it’s not working as we may expect. Can you identify the problem?

a = 1

b = 0

try:

print("I was here")

if b == 0:

raise ValueError("b must be different than zero.")

a / b

print("Was I here?")

except:

print("Something wrong happen")

I was here

Something wrong happen

3. Debugging in Jupyter¶

Jupyter allow us to do post-mortem debugging with the %debug command. This is a wrapper around the basic pdb debugger that ships with the Python language.

def inverse(x):

return 1/x

y = inverse(0)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [12], in <module>

----> 1 y = inverse(0)

Input In [9], in inverse(x)

1 def inverse(x):

----> 2 return 1/x

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

%debug

> /tmp/ipykernel_111/2900781285.py(2)inverse()

1 def inverse(x):

----> 2 return 1/x

ipdb> w

/tmp/ipykernel_111/2697043687.py(1)<module>()

----> 1 y = inverse(0)

> /tmp/ipykernel_111/2900781285.py(2)inverse()

1 def inverse(x):

----> 2 return 1/x

ipdb> !x

0

ipdb> q

y

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

Input In [66], in <module>

----> 1 y

NameError: name 'y' is not defined

Now, JupyterLab also includes a debugger we can use.

Exercise¶

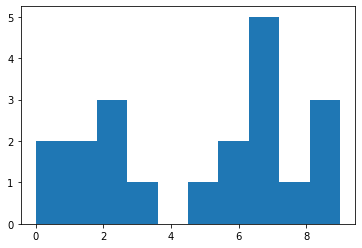

Write a function that takes a list of numbers (integers) and returns something that looks like an histogram of the data. For example, For the following list

L = [1,1,2,2,2]

You can return something that allow us to count the number of repetitions, for example

{1: 2, 2: 3}

(for the output of this function, you can also propose a different data structure or you can even try to make a plot of the histogram) Try to include arguments such as the number of bins or the spacing between them or a variable that indicates if the histogram has to be normalized (divided by the total number of elements, such that the total mass of the histogram is 1).

When writing your function, remember that sometimes less is more. Following Andy Oram and Greg Wilson advice in Beautiful Code,

A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

### def ... ():

### """

### ...

### """

### return ...

Then try your function on the following examples

import numpy as np

L0 = np.random.randint(0,10,20)

L1 = np.random.uniform(0,1,20)

L2 = []

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.hist(L0);